Vietnamese Language, A Long History

http://www.vnstyle.vdc.com.vn/myhomeland/traceback/Vietnamese_language.html

Some 3,000 years ago, communities of Mon-Khmer and Tay people merged in the northern Red River and Ma River Deltas. These two groups developed a shared language, known as Viet-Muong, which was composed of two main dialects. Lowlanders spoke what was known as the “City” dialect, while people in midland and mountain regions spoke the “Highlanders” dialect.

About 60 percent of modern Vietnamese words are of Chinese origin. Many basic words, like geographical terms, were adopted from monotonal Mon-Khmer languages, while tonality came from Tai. In Vietnamese, each syllable has one of six tones, which completely alters the meaning of the word, and one, two or three of 11 distinct vowel sounds. This is a complicated language, which, not surprisingly, has a complicated past.

THE CHINESE

The Chinese annexed Giao Chi (the Tonkin Delta) in 111 A.D. In a bid to assimilate the lowland Viets, they introduced a Chinese-style administrative system headed by Chinese governors, and opened schools to teach Chinese characters. During the 1,000 years of Chinese rule, while Han (classical Chinese) was the official written language, the spoken language continued to develop. The City dialect became the common Viet language, while the Highlanders dialect developed into the present Muong language. By the l0th century, when the Viets recovered their independence and established the nation of Dai Viet, the linguistic spilt between Viet and Muong was complete.

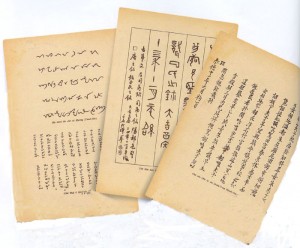

Through the following ten centuries of national independence, the Vietnamese imperial court and ruling classes continued to emulate Chinese cultural practices. Civil service exams and academic literature were written in Chinese characters. The spoken language, however, was Vietnamese, and here arose a paradox: the script approved by the imperial court was not used to transcribe the national language. Instead, the Viets adapted Chinese characters into their own script, ch÷ n«m, a half-phonetic and half-ideographic writing system.

According to the annals, Han Thuyen became the first poet to write in ch÷ n«m at the end of the 13th century. Chinese characters were still used for Chinese-style Tang dynasty poetry and for literary prose, such as Hoang Le Nhat Thong Chi (A Tale of the Later Le Dynasty), Truyen Ky Man Luc (A Random Collection of Fantastic Stories and Linh Nam Trich Quai, (A Collection of the Supernatural Beings of Linh Nam).

In the 17th and 18th centuries, poets used ch÷ n«m to write some of Vietnam’s most famous literary classics, including narrative poems like Nguyen Du’s Kim Van Kieu (The Tale of Kieu), and Chinh Phu Ngam (Laments of a Warrior’s Wife), a long lyrical poem translated from the original Chinese by Doan Thi Diem, a woman poet.

However, while many poems were written in ch÷ n«m, most other texts were written in Han characters. In fact, the mandarin class held national and popular culture in such contempt that, at one point, ch÷ n«m was officially banned. Since there was no official, uniform system for transcribing the Vietnamese language with ch÷ n«m, authors developed their own rules. This has led to many interpretations of literature written in ch÷ n«m.

LOAN WORDS

Due to frequent contacts between Vietnam and China, the Vietnamese language absorbed many Han words. Today, many of these “loan-words” have been Vietnamized to such an extent that few people are aware of their Chinese origins. Examples include tien (money), hµng (goods/merchandise), chî (market), and mïa (season). A second group of literary terms, known as “Sino-Vietnamese” words, was assimilated into Vietnamese during the Tang era (5th to 7th century). These terms are incompletely Vietnamized. When speaking, one may not mix these two types of words.

For example, since a one-syllable “pure” Vietnamese word for mountain (nói) already exists, one should not use the Chinese counterpart (s¬n-which also means mountain) to build a sentence like “T«i lªn s¬n” (I climb the mountain). The word nói must be used instead. But, one may use the Chinese synonym s¬n to replace nói in two-syllable words, such as in the sentence: “Cã c« s¬n n÷ ë vïng s¬n cíc h¸t bµi s¬n ca trong mét s¬n tr¹i”. (There was a highland girl in a mountain area who was singing a mountain song at a mountain farm).

EUROPEAN INFLUENCE

|

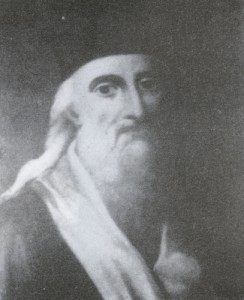

| Alexandre De Rhodes |

The Roman-based script used in Vietnam today dates back to the 17th century. French, Portuguese and Spanish Catholic missionaries, aided by Vietnamese preachers, developed a new writing system as a means of spreading the gospel to a wider audience. The man credited with developing the current Roman based ch÷ quèc ng÷ (script of the national language) is Alexandre De Rhodes, a Frecnh Jesuit missionary who came to Vietnam in 1627. Within six months of his arrival, De Rhodes was reportedly preaching in fluent Vietnamese.

When developing quèc ng÷, De Rhodes and his fellow missionaries faced two challenges. First, since Vietnamese has six tones, they had to add diacritical marks. Second, they had to transcribe each monosyllabic word separately, which differed from the ideographic and thus polysyllabic transcription of n«m script.

At first, Confucian scholars resisted the adoption of quèc ng÷. The spread of this easy to learn script undermined their power, which was based in traditional scholarship written in Han characters or ch÷ n«m. Later, budding nationalists also had reservations about quèc ng÷, calling it a ‘worm-or-cricket-like script created by imperialists”. But while few common people could read or write ch÷ n«m, the masses readily adopted quèc ng÷. Thus, those same intellectuals who had first denounced quèc ng÷, later saw it a convenient weapon in the fight against colonialism.

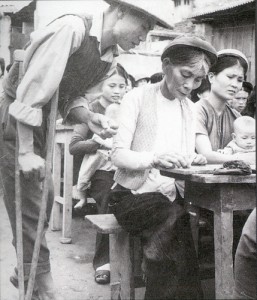

The leaders of a movement called §«ng Kinh NghÜa Thôc (the Free School of Dong Kinh), which arose in the first decade of the 20th century, launched a campaign to teach the massed about European civilization and quèc ng÷. Nguyen Quyen, one of the group’s members described their goals as follows:

A popula rizing class rizing class |

To open a new era, we turn to the new learning

To welcome this new movement and build a new life for the people with new books, new media, new writing…

In the first half of the 20th century, quoc ngu greatly facilitated contact between Vietnamese and Western cultures. Following Vietnam’s independence from the French, Vietnamese Government officially recognized quoc ngu as the nation’s official writing system. Uncle Ho also advocated movement to Vietnamize words, and founded the B×nh D©n Häc Vô (Department for Popularizing Culture) to launch a campaign to eliminate illiteracy.

Like every living language, Vietnamese will continue to evolve, absorbing and Vietnamizing words from other cultures.

An evening class of Vietnamese farmers